Highly-measurable upside vs. immeasurable downside

There's this pattern that emerges in engineering, marketing, and a lot of other things that we do. I suspect somebody has already named it - some law or maxim - but I've not seen it written somewhere. I describe it as the "highly-measurable upside vs. the immeasurable downside."

It goes like this: there's a thing that you try - an experiment or a change to a process - and the metrics tell you it's good. The positive impact of this is highly measurable. You get instant, fast feedback that the change is worthwhile. Everyone would agree you should keep the change.

But there's this niggling fear in the back of your mind that makes you feel uneasy with the change. You worry about some backfire or downside. Often, that downside is extremely hard to measure. You almost feel silly for worrying about it, since the data for the positive case is so convincing, and there's no data to be found for the negative case. In a company that's very much geared around KPI's or OKR's and measuring success, it's really hard to even raise an objection.

I see this a lot in marketing, but also in engineering, so here's a few examples.

Example 1

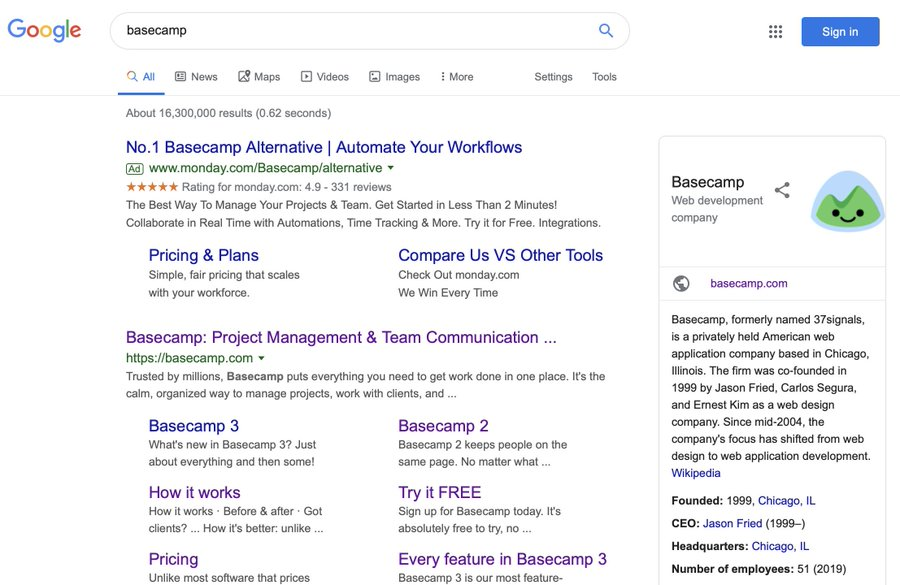

A self-proclaimed marketing guru suggests that since people like to Google your competitors, you should run a Google Ad for their brand. Case study - Monday.com advertising on searches for "Basecamp":

The "highly measurable upside" to Monday in doing this is clear. Within minutes the graphs are all pointing up - impressions, clicks, conversions. The CMO can loudly proclaim the tactic is a success, and all the data backs them up.

The "immeasurable downside" is far less obvious. If I were a potential Monday customer, but had any affinity to Basecamp, I'd see this as predatory. Especially when it's a clear case of VC-funded mega corp vs. boostrapped underdog. For companies proclaiming themselves as "leaders", it's not convincing to me. It's certainly not classy.

Putting aside whether Monday is in the right (editor: they aren't!), the point is that there's a lot of data that supports continuing the tactic, and very little to argue against it.

Measurable upside: impressions and clicks. A thousand charts in Google Analytics will tell you to keep it up. You'll hit your MQL quota and get that bonus.

Immeasurable downside: all the people who don't click your ad, and now have a bad impression of you, the word of mouth you'll miss out on, and the great candidates who won't apply for you, because you come off a little desperate.

Much more than engineering, marketing is actually a domain in which a team's performance is far more quantiatively measurable. But nearly all the measurements available seem to only argue for the positive case. It takes a really long time - a year maybe - for things like brand damage to turn up on a chart.

Example 2: Engineering

Most forms of technical debt fall into this trap too: shipping the feature is highly measurable, but the technical debt isn't.

While we all dream of writing some gnarly code to 10x the performance of a critical part of the system, in the real world most performance improvements come from not doing dumb stuff. But occasionally, you can get some big improvements by writing the code in a way that makes it much more difficult to maintain.

Measurable upside: The code is 10x faster.

Immeasurable downside: The code is harder to understand now, and we're afraid to make any changes to it, so we're not innovating in that space anymore and it's rot.

What can we do about it?

Probably the only thing we can do is to have a strong set of values and stick to them. Do we value our brand over our quartely OKR's? Do we value long term maintainability and readability over performance? That's up to each company to decide, and to promote.

Metrics can help to reassure us that the work we're doing is having the intended effect, but they absolutely shouldn't be used to decide whether to do something in the first place, or whether to continue doing something when your gut starts to question it. Google is famously metric-driven; "Don't be evil" was probably the counter-balance they needed.

As an individual, listen to your gut and speak up if you have concerns about potential downsides that fly in the face of the positive metrics. Do work that you're proud of first, improve metrics second.

As a company, don't use metrics as the primary way you manage people and their performance. Focus on the quality and fidelity of their work. Use metrics to double-check your assumptions and to celebrate, but don't use them to manage. At least this is our philosophy.